More on LTC Lakin from the motions hearing

I posted a tease here, and it didn’t take long for Dwight “My Liege” Sullivan to crack the code.

In other words, Judge Lind used the word “embarrassment” in precisely the political question doctrine context (and using almost exactly the same words) as CAAF in New and the Supremes in Baker v. Carr. And all the breathless birther commentary saying that she was attempting to avoid personal embarrassment to President Obama is just so much guano.

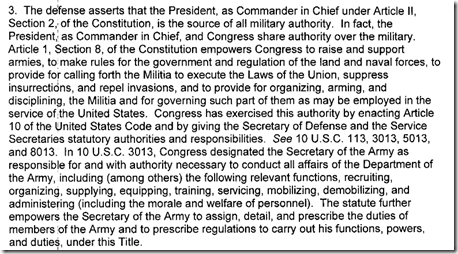

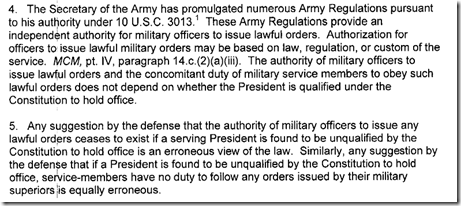

As always one has to admire Dwight’s pithy commentary. OK, here is some more (working from a “bigger” computer, netbooks have some limitations).

Should LTC Lakin be embarrassed?

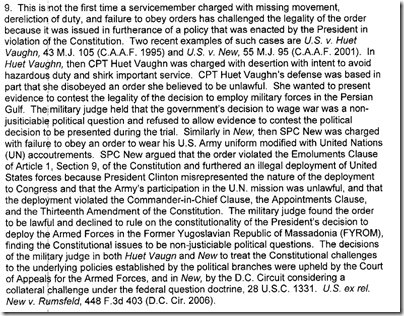

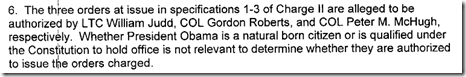

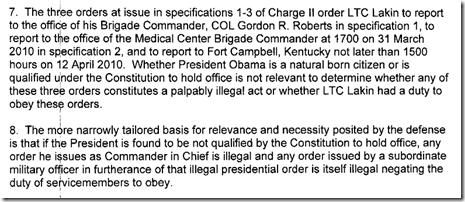

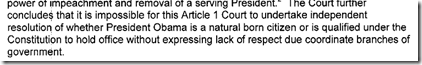

Some reporting of last weeks Article 39(a), UCMJ, hearing appears to attribute the military judge’s ruling to a desire to save the president embarrassment. I believe this is a gross distortion of a small part of what the military judge said. I was there and heard her read her findings and conclusions which were then made a part of the record of trial and available to the parties. These are the relevant references.

The above is from the discussion of the political question doctrine. The sole use of the word embarrassment is here:

Does the above compute with what World Net Daily or others have said? You decide.

Does the above compute with what World Net Daily or others have said? You decide.

Humor in military uniform law

Here is a link to the 3 September 2010 Federal Register for the recent MCM amendments signed by The President.

And the humor you say – – – –

Hat tip to Native and Natural Born Citizenship Explored blog (a not a birther blog).

Coast Guard boat crash update

San Diego online reports:

Three San Diego Coast Guard boat crew members will face the military version of a preliminary hearing beginning Tuesday for the Dec. 20 crash that killed an 8-year-old Rancho Peñasquitos boy.

The top charge, involuntary manslaughter, is against Ramos. Howell and Rasmussen are charged with negligent homicide. Coast Guard officials have said it may be the first time in modern memory that any member of the Coast Guard has been charged with manslaughter for actions taken in the course of duty.

Up periscope

Navy Times reports:

The Navy says it’s unlikely to charge the parent who ran over and killed a 2-year-old at Norfolk Naval Station.

But NCIS is still investigating.

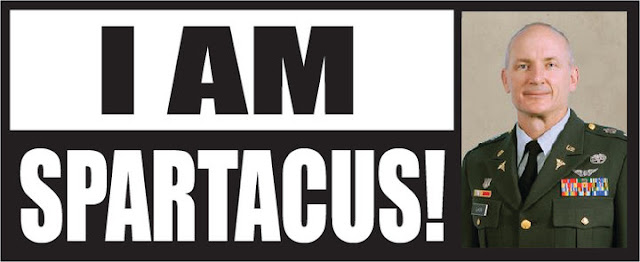

LTC Lakin continues to spin

Found at birtherreport.com.

LTC Lakin and Mr. Jensen will be on the Barry Farber radio tonight at 2000.

Apparently the “embarrsassment” language was intended by the judge to alert Congress that they need to begin impeachment proceedings.

LTC Lakin is spinning

The spinning has begun, and yes there’s a pun in there, or at least an attempted one. Based on cherry-picked comments from a number of Lakin supporters it appears that all of this is merely the military judge saving the President “embarrassment.” They are grasping at a straw as a way to explain a complete and utter refutation of what they have been trying to incorrectly advertize as the state of military law, assuming they were present. Some comments about the military judge as an individual have become so personal, so obnoxious, and downright nasty that I have decided to remove or not post such comments. Yes, this is a change from my normal attitude of let what’s said be said and the sayer and his/her worth as a person be evaluated.

PERHAPS SOMEONE COULD BE ENCOURAGED TO MAKE THE WRITTEN FINDINGS PUBLICLY AVAILABLE?

I was present for the “40 minute” reading of her written findings and conclusions. These written findings and conclusions are now part of the record of trial, and are also now available to Jensen, LTC Lakin, and the prosecutors. Perhaps APF could post the findings so we can see just how badly the military judge ruled – APF let’s get those wrong headed arguments of the judge out in the open where the full text can be read and dissected?

NMCCA decisions

NMCCA has released a number of decisions. Several have providency issues and issues not raised by appellate counsel.

United States v. Messias. The court set-aside a finding of guilty to because of an inadequate providence inquiry. No sentence relief granted.

While the providence inquiry establishes facts sufficient to demonstrate that the appellant drove on base and that he believed the driving to be wrongful, there are no facts developed which establish either the invalidity of the appellant’s license, if any, or in the alternative, his failure to have a valid license in his possession. We cannot infer either eventuality from this record. We are left with a substantial basis in fact to question this plea and conclude the military judge abused his discretion in accepting this plea on these facts.

Court-Martial Trial Practice Blog

Court-Martial Trial Practice Blog